by Kate Dernocoeur, guest blogger

It was a nice mid-winter day in July when my friend Steeve and I set out from Namibia’s capital city of Windhoek with our exceptional guide, Ian Brown. This meant the temperatures were nicely tolerable, instead of the extreme swelter of summer. The week ahead would take us around the southern half of the driest sub-Saharan country in Africa, where most areas get less than 2″ of rain per year.

Namibians are proud that their roads are among the finest in Africa, and it proved true on our 1,200-mile tour. We headed out the B1 road, stopping along the way at Rehoboth, a town famous for its “Baster” people (Afrikaans for bastard, and a point of pride for some mixed-race people). Next we crossed over the Tropic of Capricorn, which marks the southern boundary of the tropics. Fun fact: “The Tropic of Capricorn is the southernmost point on Earth where the sun is directly overhead during the December solstice.” [source: https://science.howstuffworks.com]

Namibia is a roughly rectangular country, 600×300-450 miles (with a long, narrow eastern extension in the north called the Zambezi Region (formerly called the Caprivi Strip). It is a little larger than twice the size of Texas. Its population of 2.653 million makes it the second-least densely populated country in the world after Mongolia. As we drove the equivalent of once around Texas that week, I knew we’d see lots of wide open spaces once we were free of the traffic and modern congestion of Windhoek (pop. 461,000).

Our route took us down the spine of the Central Plateau, which is bracketed by the Kalahari Desert to the east and the Namib Desert, the oldest desert in the world, to the west. Our first stop was Camelthorn Lodge, an eco-tourism place in the quiet, starlit middle of the savannah and scrub country host to, well, not much. Only one percent of the land in Namibia is arable, and sustenance comes more from mining (think diamonds and precious metals), animal husbandry (sheep, goats, and some beef), manufacturing (mostly fish along the coast), and a rising tide of tourism. Despite hefty levels of poverty for about 65 percent of the population, Namibia enjoys a relatively tame and safe reputation. Ian, a master guide for more than 30 years in his home country, calls it “Africa Lite.”

I’ve always loved road trips, and this one was memorable for the expanses we traversed from place to place. After a sundowner game drive at Camelthorn Lodge and a glorious morning sunrise (when I saw my first-ever meerkats!), we headed for Fish River Canyon, nearly 300 miles farther south. Fish River Canyon is the largest in Africa, and many compare it (reasonably) with Arizona’s Grand Canyon. After an exquisite night in my own private cabin, I hiked halfway down from the rim and back with a guide and a German family—a real exertion that yielded glorious silence and magnificence.

Next, we drove 270 miles to the coastal town of Luderitz. Both the name and the architecture highlight the historical 1884-1915 German occupation of Namibia (when they called it German South West Africa). German colonialism was a sad, brutal chapter, and from 1904 to 1907, a genocide little-known to the outside world occurred between the Germans and Nama and Herero resisters. Half the population of Nama people and 80 percent of the Herero people–about 75,000 people in all—were murdered.

At the close of World War I in 1920, the League of Nations arranged for Namibia to be “administered” by South Africa, and it became known as South West Africa. South African laws were imposed, including apartheid starting in 1948. In Windhoek, blacks were forced to relocate to the outskirts. Their settlement was named Katutura, which means “we have no permanent dwelling place.” Years of guerilla warfare by freedom fighters finally led to Namibian independence on March 21, 1990. A formal apology from Germany for the Namibian genocide was made in 2004.

The pain suffered over the decades and the resilience needed for many people to keep going is deeply moving. Even in this so-called “Africa Lite” country, there exists enormous and long-standing trauma from colonialism.

We left Luderitz for a tour of the nearby ghost town of Kolmanskop. A diamond found there in 1908 led to a 20-year mining frenzy, but it all ended with depletion and World War I—plus the discovery of an even better diamond field to the south near the outlet of the Orange River. Since then, Kolmanskop has been gradually disappearing, reclaimed by the desert sands.

Although the iconic African wild animals of Namibia mostly reside in the north, we often saw oryx, zebra, ostriches lots of other cool birds, and some jackals along the road. And then there were the wild horses! The origin of the Namib Desert Horse herd of 90-150 feral animals is unclear. Theories include they were released from camps and farms during World War I, or maybe they stemmed from cavalry breeding programs. Who knows? Considered an “exotic species,” these hardy horses live on the Garub Plains and courteously showed themselves as we passed.

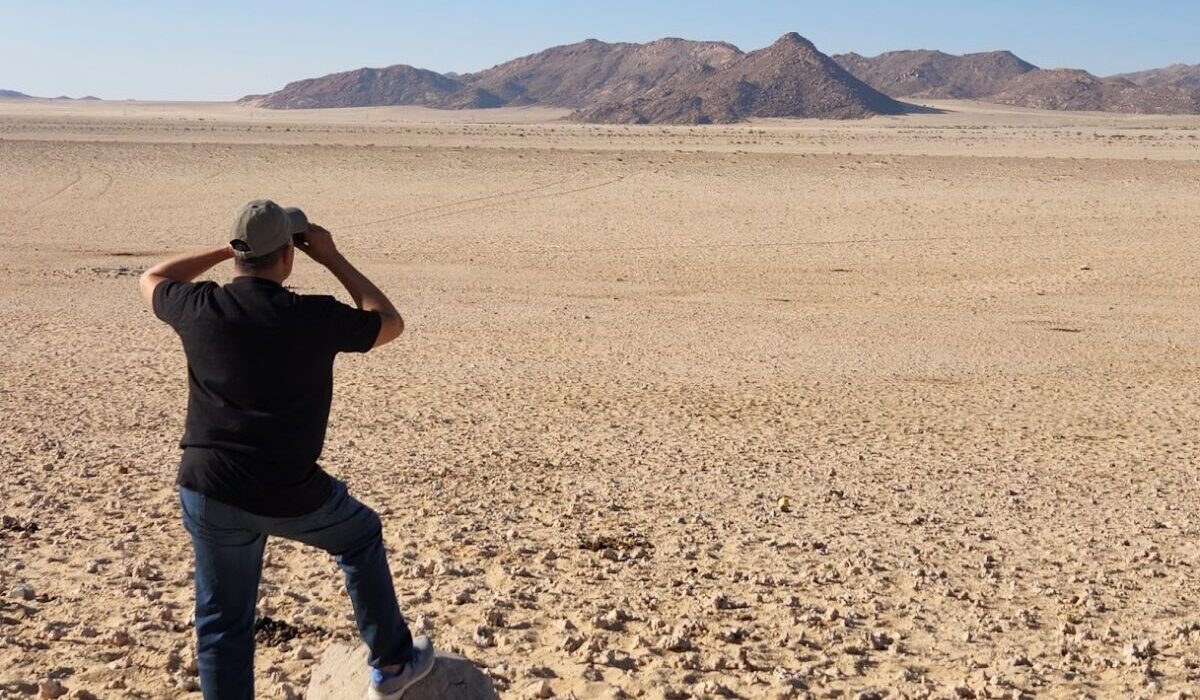

By then, we were on our way 200 miles up to Sesriem and Sossusvlei, home to the world’s highest sand dunes. The stunning area more than deserved the two nights we camped there, even though our second morning involved packing up in a raging sandstorm! A few hours and 190 miles later, after a stop in the roadhouse-hamlet of Solitaire for its famous apple streudel, we left Ian’s care and headed for Steeve’s apartment to regroup for Namibia, Part 2 (the Northern Tour).

Come back next week for Kate’s blog post about the Northern Tour.

Kate Dernocoeur had a quiet (and healthy, thank goodness) COVID year at home on her rural road in Lowell, Michigan, but is happy to be free again to get out to the wild and beautiful places. This post originally appeared in her blog, “Generally Write” at www.katedernocoeur.com

Kate Dernocoeur had a quiet (and healthy, thank goodness) COVID year at home on her rural road in Lowell, Michigan, but is happy to be free again to get out to the wild and beautiful places. This post originally appeared in her blog, “Generally Write” at www.katedernocoeur.com